100th BATTALION, 442nd REGIMENTAL COMBAT TEAM and MILITARY INTELLIGENCE SERVICE

By Minoru “Min” Yanagihashi, PhD

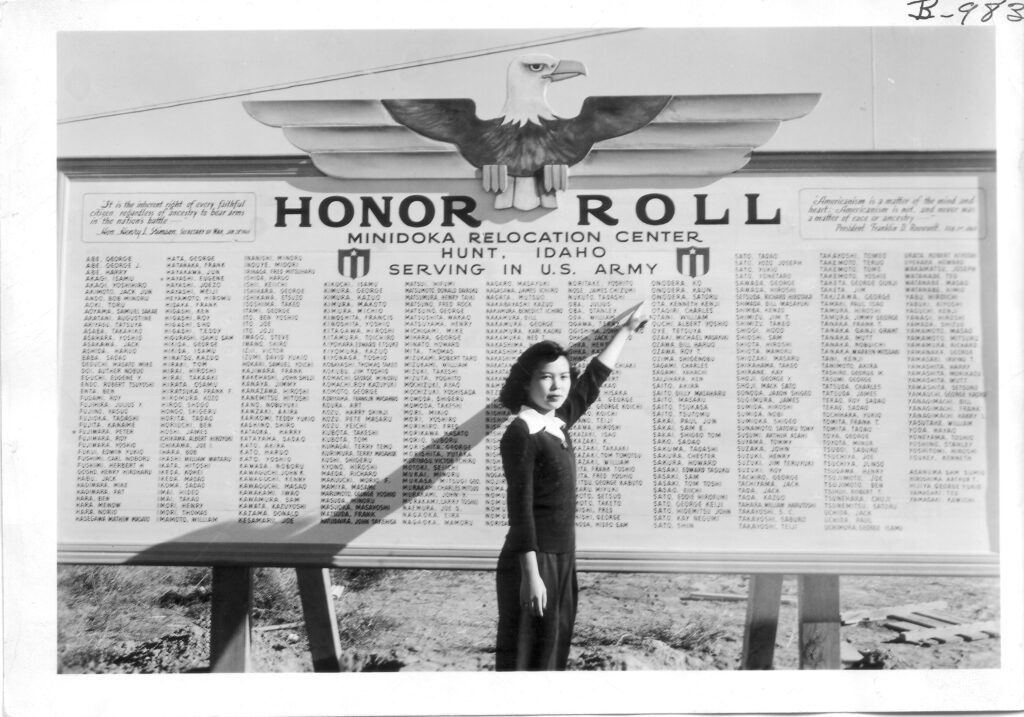

After the Pearl Harbor attack, Nisei men faced vexing questions when the call came for volunteers to serve in the US Army. They asked themselves, “Why should I serve when I’m in a concentration camp with my family and denied our fundamental rights?” “How can I when I’m encountering discrimination and viewed with suspicion?” A few responded by refusing the country that disrespected them. However, a majority reacted by changing the questions into a challenge. They would demonstrate their loyalty by enlisting in the army, thereby helping to free all Nikkei from the concentration camps. It became a test of loyalty for Nisei enlistees, and around 33,000 accepted the challenge.

In nineteen months of combat, the 100th and 442nd compiled an outstanding record. With eighteen thousand individual awards, it is the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in American military history. Twenty-one Medals of Honor, 9,486 Purple Hearts, and seven Presidential Unit Citations are among its notable decorations. It came at a cost of about eight hundred killed or missing in action. Its legacy lives on in memorials, museum displays, books and other printed materials, digitized oral interviews, movies, documentaries, and countless other media formats. The 100th Battalion of the 442nd RCT is occasionally activated and is based at Fort Shafter, Honolulu, Hawai’i. It is one of the rare units from World War II with a long continuous record that extends to this day.

It came late but military historians and other writers have extolled the achievements of the MIS linguists. Tangible awards were bestowed on the veterans. They won over five hundred combat medals, fifty-eight Purple Hearts, and one Presidential Unit Citation (only one because they were in small groupings; nevertheless, they were recognized for being part of eighty units that received the Presidential Unit Citation). Their legacy lives on. There is a MIS museum in the Presidio, and the MISLS continues today as the Defense Language Institute, one of the world’s foremost language schools.

The story of the Nisei soldiers began in Hawai’i. Before the war, five thousand Nisei were members of the National Guard of Hawai’i. There was also a contingent of Nisei in the University of Hawai’i Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). Once the war started, the National Guard of Hawai’i was federalized and became the Hawai’i Territorial Guard (HTG). While the Japanese attack was underway, men of the HTG reported for duty. They were assigned to military installations, beaches, and strategic locations. Some officials began to complain about “Japs” serving as guards. The military reacted by taking away their weapons and assigning them with kitchen and yard work. Suspicion persisted, and the Nisei in the HTG were discharged, which incensed the Nisei since they were being treated as “enemy aliens” rather than loyal Americans. Community activists and influencers supported the Nisei, arguing that they be allowed to serve their country. After much cajoling, the military agreed to form a noncombat labor battalion, the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV). It was composed of men discharged from the HTG and the university ROTC.

Further persuasion dissuaded the authorities from their lingering doubts about the loyalty of the Nisei. Finally, approval was given to develop an all-Hawaii Nisei combat unit. Initially, it was a provisional battalion. The unit was shipped out secretly on June 4, 1942, and upon arrival in Oakland, California, it was officially designated as the 100th Infantry Battalion.

The 100th Infantry Battalion

Basic training was at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, and after six months, the 100th was transferred to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for further training. Combat deployment of the 100th began on September 22, 1943, with the landing on the beachhead at Salerno in (southern Italy. Its first major engagement was the capture of Benevento. In this battle, the 100th gained a reputation as a courageous and effective military unit. What followed was the toughest battle the 100th would face—the capture of Monte Cassino. The monastery on top of the mountain was fortified by the Germans with the slopes mined and covered by machine gun fire. Heavy fighting took its toll, and the size of the 100th was reduced to half. From this time, the 100th was the “Purple Heart Battalion.” Losses were made up by replacements from the 442nd, and with these replacements the 100th became a new unit. The next deployment was at Anzio beachhead. A stalemate resulted for two months until the allies broke through, opening the road to Rome. But the 100th didn’t have the pleasure of marching into Rome. The 100th was sent northwest of Rome to Civitavecchia, where they met the newly arrived 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT). That same day, June 11, 1944, the 100th became the 1st Battalion of the 442nd RCT, but because of its illustrious combat record, it was allowed to keep its original designation. Henceforth, it would be the 100th/442nd, but this was awkward wording, so from July 1944, whenever the word “442nd” was used, it included the 100th. They were now fighting together as one team.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team

But what about the origin, organization, and training of the 442nd? It took a while before authorization was given to form an all-Nisei combat unit. At the beginning, personnel would be volunteers from Hawai’i and the mainland. The response in Hawai’i was great, but poor on the mainland. This was understandable, given the fact that in Hawai’i, few Japanese were incarcerated, whereas almost all the Nikkei on the mainland were in concentration camps. As a result, about two-thirds of the first contingent were from Hawai’i. It was only with the draft that the numbers from the mainland improved.

“Go for Broke” was adopted as its motto, meaning “all or nothing” in Hawaiian pidgin English. Although the 442nd and the 100th were led by Caucasian officers, it did not present a problem, for the white officers understood and had good relationships with their troops. But the Nisei had a problem among themselves. The Hawai’i Nisei differed in their speech, mannerisms, and disposition from their mainland counterpart. Fighting broke out during training. The mainlanders were called “kotonks,” a pidgin-derived word, to describe the sound made by a mainlander’s head as it strikes the ground — the sound made by a hollow head. The Hawaiian Nisei were called “buddhaheads,” referring to the bald head of a Buddhist priest or buta, the Japanese word for “pig.” Once they entered combat, the pejorative meaning disappeared, and the words became a friendly way to differentiate the Hawai’i Nisei from the mainland Nisei.

The 442nd differed in organization from the usual US infantry regiment. For one thing, it was all Nisei. Furthermore, it was an augmented regiment. Besides the unique 100th Infantry Battalion, there are the 2nd Infantry and 3rd Infantry Battalions. Included in the organization are the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 232nd Combat Engineer Company, Anti-tank Company, Cannon Company, Service Company, plus Medical Detachment and Headquarters Company.

Training for the 442nd took place at Camp Shelby from May 1943 to April 1944. The unit was deployed to Italy in June 1944, and the first battle the 100th and 442nd fought together was in August 1944 for Hill 140, referred to as “Little Cassino.” Shortly thereafter, the 442nd was pulled from northern Italy and sent to southern France, where it joined the 7th Army. The 442nd was moved to the Vosges Mountains, where it fought its most brutal and consequential battle from October to November 1944. Previously, the 442nd had fought on the hilly plains of Italy, but the Vosges differed with dense forest, rain, and mud. After liberating the towns of Bruyeres, Belmont, and Biffontaine, the 442nd was sent to rescue the “Lost Battalion” of the 36th “Texas” Division, which was trapped and running out of food and ammunition. Two previous attempts had failed. The 442nd entered the forest and after five days of intense fighting, 211 Texans were rescued, but at the high cost of more than 800 casualties. Major General John Dahlquist, who ordered the 442nd to do the rescue, was criticized by officers in his division for using the 442nd as cannon fodder. The Nisei didn’t complain; they just followed orders.

General Mark W. Clark of the Fifth Army wanted the 442nd in Italy and got his wish. The 442nd returned to Italy minus the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion. The 522nd was attached to the 7th Army and was used in the invasion of Germany. The 522nd served as a roving battalion supporting various units and was the only Nisei outfit to fight on German soil. It participated in liberating subunits of the Dachau concentration camp. Meanwhile, in Italy, the 442nd was used to breakthrough the Gothic Line, the last hardened defense before the German border. Once the Gothic Line was penetrated, the Germans retreated and began to surrender en masse. The war in Italy ended on May 2, 1945, and five days later, it ended throughout Europe.

Military Intelligence Service

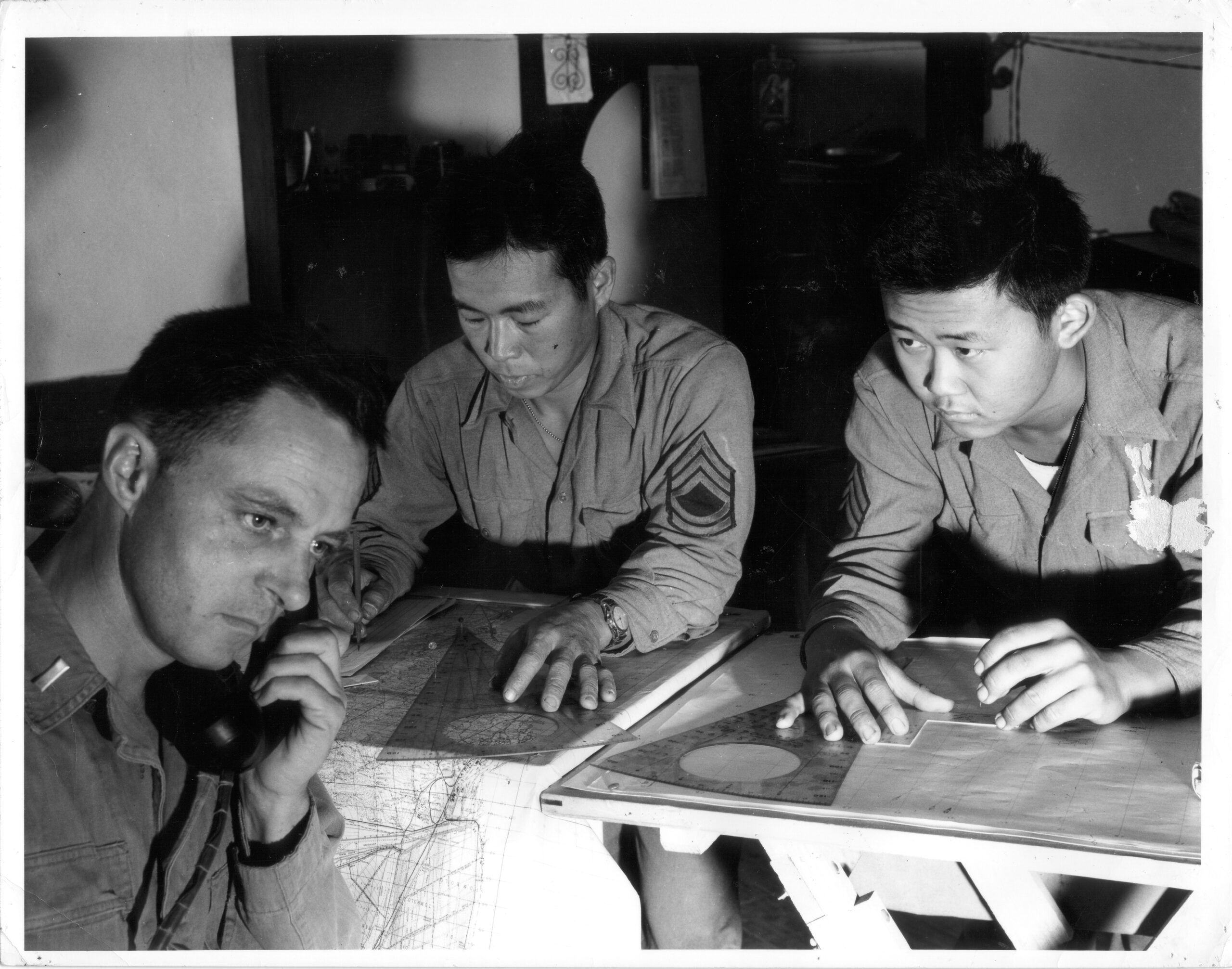

Compared to the 100th and 442nd, not much is known about the Nisei servicemen who served with the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). Most of their operations were clandestine, shrouded in secrecy, and involved a small number of men, usually two or three or a small team. Furthermore, they were scattered throughout the Pacific region and on the Asian continent. It was only in 1972 that the secrecy was lifted. Therefore, the recognition came late, but today we have a better understanding of their accomplishments.

With the deterioration in US-Japan relationship and the possibility of war, army planners in the late 1930s became concerned about the lack of personnel with command of the Japanese language. A survey revealed almost a total absence of soldiers proficient in Japanese, and among the Nisei personnel, only a few were skilled with the language. To meet the need, a language school was established in November 1941, a month before Pearl Harbor, at the Presidio of San Francisco. There were sixty students in the first class, fifty-eight Nisei and two Caucasians. Due to increasing anti-Japanese sentiments and Executive Order 9066, the school was moved to Camp Savage, Minnesota and was named the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS). Because of heavy demand for its students, MISLS soon outgrew its facilities and moved to Fort Snelling, Minnesota. MISLS continued until 1946 and produced over six thousand graduates.

Graduates were assigned to units in all the branches of the US armed forces. They translated, acted as interpreters and interrogators, and produced propaganda materials. The MIS Nisei worked under difficult conditions. They fought an enemy who looked like them and could easily be mistaken for one. Moreover, some unit commanders and fellow soldiers were suspicious and didn’t trust them.

Several feats of the Nisei linguists were consequential for the war and of historic importance. In the Guadalcanal Campaign, vital data gleaned from documents, letters, and interrogations of POWs provided information that helped turn the tide of battles. At Guadalcanal the importance of the MIS Nisei was acknowledged, and unit commanders began to request their presence. Especially significant was their improved skills in interrogation techniques. Another accomplishment was Technical Sergeant Kazuo Yamane’s discovery and recognition of the importance of a document listing the Japanese inventory and storage, as well as the manufacturing potential of weapons and ammunition. Information from this source was used in the B-29 bombing missions. The MIA linguist’s translation of the “Z Plan” was probably most consequential, the final defense strategy of the Japanese Imperial Navy. The portfolio containing the Z Plan was found by Filipinos and eventually ended up at the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS) in Brisbane, Australia. Copies of the translated Z Plan were sent to all pertinent commanders. The translated Z Plan played a significant part in the American victory in the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

(Courtesy of the Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army.)

In the Occupation of Japan, over three thousand Nisei linguists served as translators, interpreters, interrogators, and investigators. Several were with the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, and a large number were with the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), General MacArthur’s headquarters. They assisted in the work on the Japanese constitution, reforming the Japanese legal and judicial system, and implementing the Occupation’s reforms in economics, local government, and education.

RESEARCH NOTES

These notes are meant to facilitate the search for ancestors or relatives, and for those who want to learn more about the 100th, 442nd, and MIS. It is not exhaustive, but enough links are provided for an extensive research.

Most of the information is available online. For the 100th and 442nd, there are works by scholars and researchers, such as Robert Asahina, Lyn Crost, Masayo Duus, James M. McCaffrey, Franklin Odo, Orville C. Shirey, C. Douglas Sterner, and David F. Bonner. The MIS sources would include the works of Joseph D. Harrington, James C. McNaughton, and David W. Swift Jr.

Museums, veteran organizations, and historical societies are vital sources. Here are some of the institutions and organizations:

Go For Broke National Education Center www.goforbroke.org

Japanese American National Museum www.janm.org

Japanese American Veterans Association (MIA only) www.javadc.org

MIS Veterans Club of Hawai’i www.misveteranshawaii.com

National Japanese American Historical Society http://www.njahs.org/

Nisei Veterans Legacy www.nvlchawaii.org

Publications from these sources tend to be ephemeral and often difficult to obtain but many are digitized and available online. They are excellent sources for photographs, oral interviews (Hanashi Oral History Collection of Go for Broke National Education Center), and testimonies.

Those researching a specific individual in the 100th and 442nd should have an organization table of the unit and a campaign map. Some companies of the 442nd had active veterans clubs, which published their own history. For example, I (”Item”) Rifle Company published their book, And Then There Were Eight, edited by Edward M. Yamasaki. It has background information, biographical data of members, brief testimonies, and many photographs. Unfortunately, these works tend to be self-published with limited copies. In the communities where the veterans resided, clubs, associations, and cultural centers may serve as depositories for personal letters, documents, and photographs. Access requires more time and effort since these organizations may not have websites.

Min is a retired professor and author of several books, including The Japanese American Experience: Change and Continuity, available through Amazon.