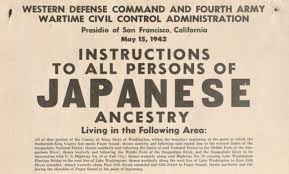

Mass incarceration of Japanese Americans

2/19/1942 to 3/20/1946

Colorado River Relocation Center, Gila River Relocation Center, Catalina Federal Honor Camp

Note: The term Relocation Center was the euphemistic official designation used by the U.S. Government, though historians and survivors have increasingly used the term “incarceration camps” or “American concentration camps” to describe the nature of these facilities where approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly detained from 1942-1945. The term “honor camp” did not reflect any special honor given to Japanese Americans. They were draft resister imprisoned for refusing military service while their families were incarcerated in camps. “Honor camp” was simply standard nomenclature for minimum-security work camps, though prisoners were under surveillance and had a strict schedule.

Min Yanagihashi, PhD

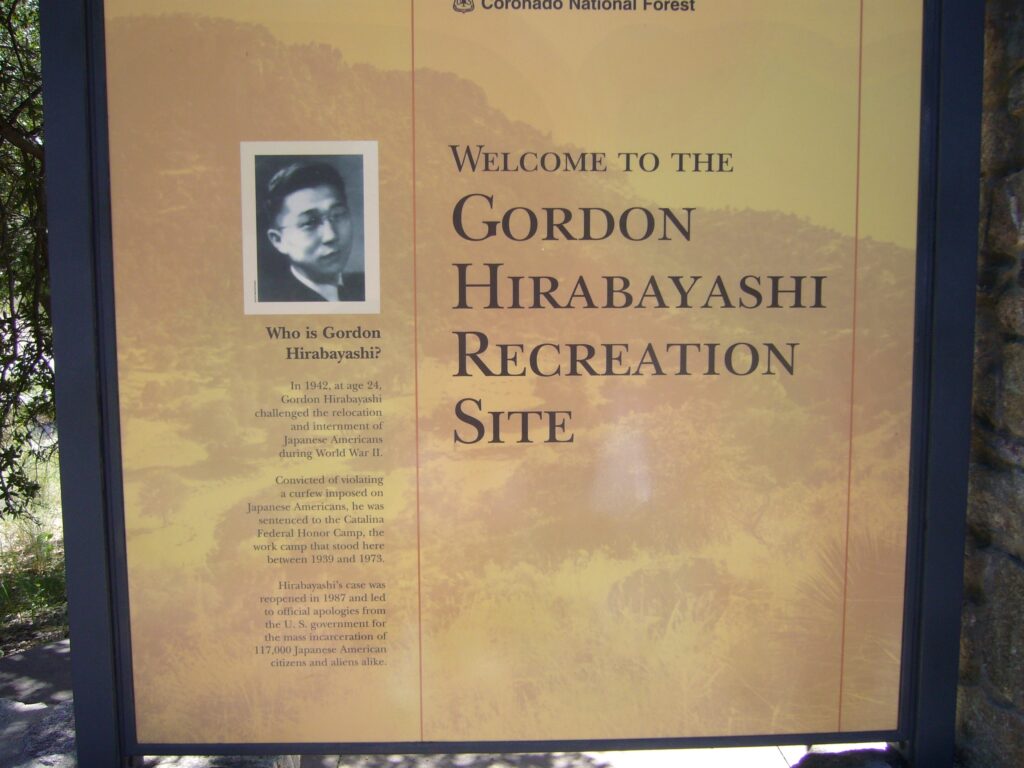

Of the three Arizona incarceration camps discussed in this section, two were similar, but the Catalina Federal Honor Camp was quite different. All three, however, served one purpose—to confine those of Japanese ancestry during World War II. Today, these sites are accessible to the public. Poston can be toured, but certain areas are farmed or used for other purposes by Native Americans. To visit Gila River, permission from the Gila River Indian Community is required, and they supply the personnel to conduct the tour. The Catalina Federal Honor Camp, renamed the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site, is open to the public. There are memorials, kiosks, and other markers. And, of course, there are traces of the former camps. Visitors can experience a vivid impression of what it was like in these camps, which cannot be fully achieved from photos and books.

Colorado River (Poston)

Poston was in northwest Arizona near the California border twelve miles south of Parker. Part of the Sonoran desert, it is hot and humid in the summer. The high humidity is due to its proximity to the Colorado River. In the winter, the days are cool and the nights bitterly cold.

The location was chosen because it is far from major cities and military facilities and easily attainable. It is on a Native American reservation, and although the tribal council opposed the use of the land for nefarious purposes, it could not stop the US government. Initially, Poston was administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), while the other nine camps were under the War Relocation Authority (WRA). BIA promised Poston would be a model community with cooperative farms and continue this way after the war. This was counter to the purposes of the WRA and disputes arose, with the WRA winning and taking full control in December 1943. The incident was confusing and disappointing to the Nikkei (Japanese).

Poston was the largest of the ten camps with a maximum population of 17,814. It was so massive it had to be divided into three camps, Poston I, Poston II, and Poston III, with Poston I twice the size of Poston II and III. It was a depressing sight with row after row of tarpaper-lined barracks, devoid of trees and shrubs because the land had been bulldozed.

There were a few protests and demonstrations against the camp administration, but they were peacefully settled. Living conditions were a constant source of irritation. The big problem was boredom and lack of purpose. But what was surprising was the resiliency and patience of the Nikkei. They made intolerable conditions a little more tolerable. Trees were planted, ponds and gardens built as landscaping beautified the surroundings. Internees built their own classrooms and school auditoriums. Big bands provided musical enjoyment and an opportunity to dance the boogie-woogie and jitterbug. Sporting events such as baseball and sumo tournaments offered additional entertainment. The organizations and club activities found in a typical American city or town, such as the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, church functions, and performing and practicing art groups were also available in the camps.

The Poston Relocation Center closed in November 1945.

Gila River

Gila River was located about fifty miles from Phoenix. It was near I-10 and the town of Sacaton by the Gila River. It was built on the Gila River Indian Reservation land, despite the tribal council’s opposition.

Gila River was comprised of two separate camps, Canal Camp on the east and Butte Camp on the west. At its peak, it had a population of 13,348. In 1944, the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas was closed, and about two thousand internees were transferred to Gila River, making it the second largest camp next to Poston.

National Archives and Records Administration

Before construction began in July 1942, two months after Poston, the land was leveled and cleared of all vegetation. In this part of the desert, there are occasional dust storms caused by strong winds with visibility minimized to a few feet. A huge problem at Gila River was the dust, which was everywhere, even within the barracks. The barracks had fine cracks caused by the shrinkage of lumber since new lumber was hastily used to construct the buildings. Nevertheless, by appearance, the Gila River camps were the best because of the use of white fiberboard sheeting on the walls and red shingles on the roof. It was also less imposing because, unlike other camps, its fences lacked barbed wire and there was only a single guard tower. When guests like Eleanor Roosevelt and WRA director Dillon Meyer wanted to see the camps, they were taken to Gila River.

The barracks were bare with no furniture, and only army cots and blankets were issued. There were no partitions and, as a result, the biggest problem was the lack of privacy. The lavatories and showers were in another communal building, and there were no stalls. The mess hall was one big noisy and crowded building. Families often could not eat together.

Similar to Poston, the residents of Gila River tried to make the conditions livable. They built a factory to produce adobe, a versatile building material made of sun-dried clay and straw bricks. For entertainment, they formed big bands, and held theater shows, including traditional Kabuki. But the biggest attraction was baseball. The “father of Japanese baseball,” Kenichi Zenimura, organized a league of thirty-two teams. He built baseball fields and coached two teams. It was said the baseball played in the internment camps was the best in Arizona at that time. Many activities helped to keep morale up and temporarily forget the miseries of camp life.

Agricultural production here was outstanding. Over one thousand internees worked on its farms. It had the largest livestock program of all the camps, and its vegetable output provided food for the camp and was also exported to the other camps.

The final segment of the Gila River Relocation Center closed in November 1945.

Catalina Federal Honor Camp

Located in the Santa Catalina Mountains, the Catalina Federal Honor Camp (now named the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site) was northeast of Tucson. The camp was established in 1939 as a prison labor camp to build the road to Mount Lemmon. It was administered by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. During World War II, it housed draft resisters and conscientious objectors. Forty-five Japanese American draft resisters from Granada (Camp Amache), Topaz, and Poston internment camps were sent to the Honor Camp. It was relatively unknown until Gordon Hirabayashi spent the last three months of his prison sentence at the Catalina camp. Hirabayashi was one of three protestors who challenged the government’s curfew and evacuation orders. All three cases went to the US Supreme Court, which ruled against them, but they were later vindicated when new evidence led to appeals.

The Catalina Federal Honor Camp had no fence or guard tower, but the prisoners were under surveillance and had a strict schedule. Living conditions were better than those of the incarceration camps, thus the term “honor,” which was the Bureau of Prison’s standard nomenclature for minimum-security work camps. All of the buildings were razed in 1970, and today it is a recreational site named after Hirabayashi. There is a kiosk that explains the history of the camp, Executive Order 9066, and the legacy of Hirabayashi.

Min is a retired professor and author of several books, including The Japanese American Experience: Change and Continuity, available through Amazon.

Resources:

Densho: https://densho.org/

Discover Nikkei: https://discovernikkei.org/

Go For Broke: https://goforbroke.org/

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/

National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/

Japanese American Military History Collective: https://ndajams.omeka.net/

Japanese American National Museum: https://www.janm.org/